World Scout Badge

The Toad and the Fleur-de-Lys

The Toad and the Fleur-de-Lys

It all began with Chlodevech who was also known as Clovis. He was a King of the Franks (481-511) who succeeded in extending his kingdom and in making Paris the capital city of his realm. In 496, to increase his power and influence, he embraced Christianity.

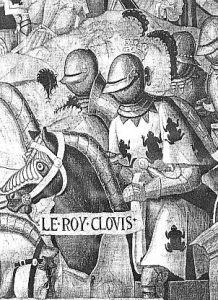

Some French historians consider Clovis’s conversion as the beginning of France as a national entity, even though many wars had to be fought and much blood had to be shed before France, the country, grew to its present size. The 1500th anniversary of Clovis’s conversion fell in the summer of 1996, with the old cathedral of the city of Reims as the centre of festivities. The event was seen as being of national significance, and was attended by the Pope. On display in the Cathedral were images of Clovis, and his royal emblem, the toad. After Clovis’s conversion he placed his Golden Toads on a blue ground, the colour of cloak of St Martin, former Bishop of the nearby town of Tours, so creating a new royal banner.

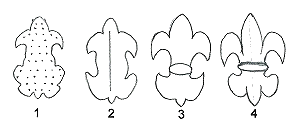

It may well have been the case that the toad, small and slippery-looking as it was, was not considered to be distinguished, dignified or stately enough to befit Royalty, but for whatever reason a slow process of restyling began (see stages 2 & 3 in the drawing shown here) until much later the emblem (stage 4) no longer resembled the original toad and its original derivation was soon forgotten. The evolved design reminded some of a special lance head which the French had introduced. With its backward-pointing two side ‘leaves’ it enabled soldiers who missed the target with their initial thrust to have a second chance on pulling the weapon back, to perhaps hook a horseman from his mount. A fair example of how, throughout the ages, human progress always seems to include better methods of mass destruction. Others, however, thought along more tranquil lines and considered the emblem to be similar to a flower, the Fleur-de-Lys or Lily-of-the-Valley, and so it was that the emblem became known as the Bourbon or the French Lily.

soldiers who missed the target with their initial thrust to have a second chance on pulling the weapon back, to perhaps hook a horseman from his mount. A fair example of how, throughout the ages, human progress always seems to include better methods of mass destruction. Others, however, thought along more tranquil lines and considered the emblem to be similar to a flower, the Fleur-de-Lys or Lily-of-the-Valley, and so it was that the emblem became known as the Bourbon or the French Lily.

The Royal House

Many French Kings could claim to be descended from Clovis, his Royal House changed names several times. Originally it was called the Merowings and then the Karolings. In 987, Hugo Capet ascended the French throne and his direct descendants occupied it until 1792 using the following family names: House of Capet (987-1328), House of Valois (1328-1589) and House of Bourbon (1589-1792 and 1815-1830). In 1792, the French Revolution began and as ‘Citoyen’ (citizen) Capet, King Louis XVI was beheaded. Napoleon’s Empire replaced the original Republic and the Bourbons came back to the throne in 1815, but could not hold on to power as, in 1830, the family were finally ousted.

Clovis’s blue flag was covered (in heraldic terms “semé” or “powdered”) with an even pattern of gold emblems – first toads, later Fleurs-de-Lys – though it too was subject to change. King Charles V (1364-1380) decided to simplify it by reducing the number of emblems to three, symbolising the Holy Trinity. The three ‘fleurs’ were depicted on either a blue or a white field. The Royal Standard, or the emblems from it, were to be seen elsewhere in Europe as other members of the Bourbon family ruled in Spain, Parma and Naples.

Sea Charts and the Compass

There have always been sailors, particularly in the Mediterranean. Some of them ventured out of that sea via Gibraltar and braved the waves of the Atlantic. Some from the Middle East sailed to England and loaded tin in Cornwall, but they saw to it that they never lost sight of the coasts. The general opinion was that the world was flat and that somewhere, far from the beaches, there was an rim over which the water cascaded. Well after the Middle Ages the Church still taught that the world was flat, with Jerusalem as its centre. Gradually however, humanity became aware of the fact that, contrary to the teachings of the Church, the world was in reality a globe. The church attempted to use its enormous influence to quell this heresy by trying to ensure that the Royal Houses of Europe did not patronise sea-faring expeditions likely to compromise the ‘flat earth’ belief and so hindered exploration and the development of chart making.

However, commercial interests, not to say greed, led to expeditions travelling ever further afield and sailors from more liberal countries began to produce charts mapping their sea voyages which they had managed to survive without falling over the edge of the world. Their navigation was much facilitated by the development of the compass and other navigational aids which, most likely, were borrowed from other cultures, such as the still very distant and mysterious Chinese.

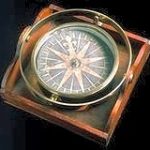

Marine Compass signed ‘Made by G. Adams, Fleet Street, London. Instrument Maker to His Majesty’, 1766 showing the stylized North Point.

Compasses and sea charts were in great demand and the science of marine cartography rapidly developed. The best available manufactures of such items were found in the Mediterranean ports and one of these was Flavio Cioga of Naples, Italy. Baden-Powell, in the American scouting magazine Boy’s Life of July 1924 wrote:

“In the Middle Ages, Charles (of Bourbon), King of Naples, being a Frenchman, had the Fleur-de-Lys as his crest. It was in his reign that Flavio Gioia, the navigator, made a mariners’ compass. In Latin, the word for North was ‘Tramontano’, so Gioia used a capital T to mark the North point, but artistically combined this with the King’s Fleur-de-Lys crest. From that time the North point has been indicated on charts and compass cards using Gioia’s device.”

Originally the Portuguese, the Italians and the Spaniards were the discoverers and explorers of the ‘New World’ but later, England and the Netherlands developed as the most important of the sea-going nations and traders. Supremacy was only achieved after many conflicts with Spain and Portugal. The need for longer sea voyages led to increasingly better charts and compasses. The English and Dutch chart makers usually indicated North by means of an artistic ‘N’ for North or Noord (Dutch) which sometimes seemed to resemble the Fleur-de-Lys. Needless to say, they never for one moment thought that by so doing they were anyway honouring French Royalty. The Bourbons had so often threatened or attacked England and the Netherlands that, not surprisingly, the sailors of the British Isles never spoke of the Lily, or Fleur-de-Lys as the symbol for North, but used the term ‘arrowhead’. The Dutch word for ‘arrowhead’ is ‘Pijlkop’ so their sailers used that term or simply ‘het Noorden’, the North.

When Piet Kroonenburg first wrote his history of the World Scout Badge, it was taken up by Scout Magazines around the world. Many readers found the article controversial and it brought protests from those who thought his conclusion that the badge of the French Royal family had evolved from a toad was insulting. One of his best friends in Scouting, the late Claude Marchal, the well-known French collector and owner of the famous Scouting and Guiding Museum in Bullet, Switzerland, was filled with indignation, and requested further publication to be stopped. As you can imagine, this was not a pleasant state of affairs for either of the two friends.

In 1996 Claude, as a good Frenchman, went to Reims and on entering the cathedral spotted the tapestry displaying King Clovis on horseback wrapped in his cloak covered with . . . a large number of toads! Much surprised, but the good sport he was, he did not hesitate. He went to a souvenir stall, found and bought a picture postcard depicting the tapestry and sent it to Piet with the short text added: ” ! ”

Baden-Powell’s choice, Arrowhead or Fleur-de-Lys?

In July 1924, B-P, by then Lord Baden-Powell, wrote an article in the US Boys’ Life magazine already quoted above. As it seems to answer so many questions and, as the source is impeccable, more of it is quoted below.

“Years ago … certain critics accused the Movement of being a military one … they said that the Scout Movement was designed to teach boys to be soldiers and they quoted as proof that the crest of the Movement was, as they described it, ‘a spearhead, the emblem of bloodshed.’ “

B-Pwas asked what he had to say about this warlike interpretation of his badge. Critics often accused Scouting of being a military organisation, doing nothing more than training boys to become ‘cannon-fodder’, and so he had his answer ready.

“The crest is a lily, the emblem of peace and purity. The history of the Fleur-de-Lys … as a badge goes back many hundreds, if not thousands or years. In ancient India it was used as symbol meaning life and resurrection, while in Egypt it was the attribute of the god Horus, about 2000 years before Christ.

“The actual meaning to be read from the Fleur-de-Lys is that it points in the right direction (and upward) turning neither to the left nor the right, since these can lead backwards again.

“The stars on the two side arms may also be read to mean that the way is blocked and wrong, though they actually stand for the two eyes of the Wolf Cub having been opened before he became a scout, when he gained his first class badge of two stars.

“Furthermore, the three points of the Fleur-de-Lys reminds the Scout of the three points of the Scout’s Promise.”

Well, there we are, a direct statement as to the origin of the badge from the horses’s mouth. Is it possible to be more definitive than that? The article however was written in 1924. Thirty-nine years earlier in 1885, when he was an adjutant in his regiment, B-P had the need to devise a badge.

Army Scout (8th Hussars) on horseback shown wearing the badge above the NCO’s ‘stripes’

“I found that the young men that joined the army as recruits were little better than half-educated boys … A few years later … I was in command of a squadron of cavalry in Ireland, and I was keen to teach my men to become practical scouts in addition to their ordinary duty of fighting in the ranks.

“I made them learn to find their way over strange country by map reading, to make maps and to write reports of what they had seen, and to do the same, each man for himself by night as well as day; to swim rivers with their horses, to cook their grub, to follow tracks, and to keep hidden while observing the enemy, and so on … I thought that some reward was due them, and so I got leave from the War Office to give each man that qualified as a scout a distinguishing badge to wear … I hit on the fleur-de-lis, or north point of the compass since, like the compass, these scouts could show the right direction for going over strange country.

“When the Boy Scouts started a few years later I used the same badge for them, for just as soldier scouts, through developing a sense of duty and manliness, they were able to be valuable helpers to the main body of the army, so the Boy Scouts could give equally valuable service to their countrymen..”

In this 1924 Boy’s Life article, B-P called his army badge the Fleur-de-Lys, but also refers to the symbol as a ‘North Point’ and explains its significance as a compass direction. Having set two hares running, the ‘fleur’ and the ‘arrowhead’, derivations to suit different audiences, B-P had created a situation where he could deny neither. By acknowledging both derivations, but giving precedence to neither, it might be thought that B-P was deliberately sitting, somewhat uncomfortably, ‘on the fence’, a position guaranteed to create confusion and controversy. Just which of the two derivations was the original concept for the most popular badge on the world?

The Army Issue

In 1897, B-P left his posting with the 13th Hussars in Dublin to command the 5th Dragoon Guards at Meerut in India. In the absence of examples of ‘Irish’ army scout badges it is tempting, but maybe foolhardy, to state categorically the first ones were made for use with the 5th Dragoons in India. Certainly, once in India B-P trained army scouts and awarded them the badge that he had designed. As far as I am aware the award remained solely for use within the 5th Hussars until after the Boer War had finished when B-P, benefiting from his increased reputation as the ‘Hero of Mafeking’ and promotion to Inspector of Cavalry, was then able to promote the idea of a badge for scouting amongst all ‘his’ cavalry regiments.

The first mention of general use of the badge is made in Army Order 19 of 1905. The following year B-P wrote an article entitled Recent steps in Cavalry Training in England in The Cavalry Journal Vol.1, No. 2 for April 26th 1906 which was officially under his direction.

“In the matter of scouting a great step has been accomplished in placing it on a sound and permanent system. All officers and men are trained as scouts: the twelve best men in a Regiment are further perfected under an ‘intelligence officer’ and are appointed to be ‘regimental scouts’. Of the remainder at least four per squadron are trained to be ‘squadron scouts’. These men are taught carefully the elements of reconnaissance, such as finding their way by map and stars, &c and are put through a large amount of practice in the field, and on long distance patrols &c in order to gain experience. On qualifying satisfactorily they are invested with a distinguishing badge, viz a brass Fleur-de-Lys (North Point) on the left arm.”

The quote is, I repeat, from 1906, one year before the Brownsea camp, two years before Scouting began and some time before anyone could have envisaged that there would be any such thing as French Boy Scouts! It has never been published previously in any Scouting context though it proves definitively that Baden-Powell was neither being evasive or duplicit in insisting on the twin derivations of his badge.

B-P’s use, in 1905, of the term ‘invested’ in the following phrase “On qualifying satisfactorily they are invested with a distinguishing badge” also has significance for modern Scouts. The verb ‘to invest’ may have been in common use in the army of the early 2Oth century, but I cannot recall any other use today in the sense it is used in Scouting, other than the Investiture of the Prince of Wales. (Interestingly there was another use of the term invest current in 1900. B-P often talked of the Boers ‘investing’ or besieging Mafeking.)

As we shall see, the army badge became the Scout badge and so it is then, to say the least, deserving of some prominence in the evolving history of the Scout Movement and its world-wide emblem.

Essentially, as far as shape is concerned, there are only two versions of the badge, one for privates and one for higher ranks. The one for ranking NCOs, sometimes corporals and above, sometimes just sergeants, had a small horizontal bar forming a cross just below the the main emblem. The badges were mainly made of brass which on occasion were polished to a high finish taking away the surface detail. (Surely it would not be a good thing for a scout to wear bright badges that would reflect in the sun!) The small version was designed for caps, whilst the larger one was worn on the right shoulder as can be seen in the postcard of the Army Scout above. Examples exist of some badges being made in silver or silver-plate finish. There was a tradition within the army of badges being commissioned from independent jewellers and even from mail-order catalogues such as Gamages. These costly privately-funded badges were, though, more often than not for officers. This may account for minor variations, or it may be that different regiments used slightly different ‘patterns’.

As was usual in the army, a cloth badge was made for dress uniforms. Whilst I have never seen any of these, I believe that some were made with metal wire, but far more commonly the badge was merely embroidered. I would be very pleased to include an image of any embroidered badge or wire badge here, if one can be located.

An article in a long-out-of-print issue of a Army Medal Collectors’ Journal is of great interest. A photocopy was kindly provided by John Woodfield, a dealer in medals and Scouting artefacts and a good friend of these Pages, who had had them sent to him over ten years ago. Unfortunately the pages contain neither a date nor the publication’s name. Clearly this was a journal of some consequence and the information the unknown author gathered in his article is

the most complete I have seen. We would be very pleased if any of our readers could supply the name and issue of the Journal so we can make proper acknowledgement.

The article contains somewhat indistinct photographs of men from different regiments wearing slightly different versions of the two designs described above. It would seem that the badge was extended to Infantry Regiments who may have been responsible for a slightly different version of the standard badge. As time went by, rules as to who was entitled to which version of the badges seem to have been ignored as photos exist with privates wearing the badge with the bar, and senior NCO’s wearing the emblem without bar.

The widespread use of the Army scout badge continued until the end of the Great War in 1918. Army scouts were used extensively during WWI with some battalions having as many as 26 men engaged in scouting, but there seemed little use for scouting in the modernised army after the war and the badge was abolished in 1921. It was however revived by the Indian Army in 1929 which used the original emblem on a green armlet for their regimental scouts.

B-P and the Fleur-de-Lys

It is one thing for B-P to have designed an Army badge in the shape of a Fleur-de-Lys/Arrowhead and quite another for this heraldic device to become associated with him in the public mind. I had always assumed that the public connection between the man and the emblem did not come about until B-P’s use of it in connection with Scouting. (See The First Scout Badge below.) In March 2007 however I was fortunate to make an eBay purchase of the silver fob ‘charm’ illustrated opposite. To be honest I did not pay it too much attention to it when purchasing other than I had never seen this design before, but of course I was aware that it showed B-P with his famous ‘Wide-Awake’ hat and was dated 1900. This put the item into the catagory of ‘Mafekania’ – the outpouring of artefacts and ephemera the followed the Relief of Mafeking on May 17th 1900, most of which seem to show him wearing his famous hat. It did not seem to matter too much at the time that B-P did not have a hat of this pattern with him in Mafeking! (See * below)

It was not until the item arrived that I realised that date ‘1900’ was in fact set upon a Fleur-de-Lys, and that much of B-P’s portrait was surrounded by a ‘swag’ of ‘Fleur-de-Lys’. In the scheme of things this may not seem very significant but it does indicate that in the public consciousness, for what ever reason, B-P was associated with the ‘Fleur-de-Lys’ emblem some seven years before he was to use the device in a Scouting connection.

The First Scout Badge

At the first experimental camp on Brownsea Island in 1907, B-P made and presented each of the participants with their own Scout badge he had made from brass sheet. These badges are evident in many photos taken on Brownsea. As can be seen from the photo opposite, the badge would appear to be in two parts and has been described as representing first and second class badges used up until 1969. B-P himself wore the same badge. The new badge appeared on his Brownsea hat which, much to the disappointment of the boys, was not his ‘wide awake’ hat of Mafeking fame*, but a trilby he was experimenting with that apparently could be packed flat. One story has it that some of the lads, seeing no further use for their badges as they returned from the island and back to their school or Boys’ Brigade unit, threw their badges over the side of the boat. (Source the present Lord Baden-Powell after talking to his cousin Donald who was on the boat.-See Lord Baden-Powell’s forward to Brownsea: B-P’s Acorn).

*As stated above B-P never wore a ‘wide awake’ hat in Mafeking. The popular misconception that he did has come about because there were no photographs available to English newspaper editors of B-P in Mafeking whilst the Siege was on and so

they and souvenir producers had to fall back on a ‘library copy’, an earlier photograph produced Elliot & Fry, taken before B-P left England for South Africa in 1899.

The first recorded representation of the Fleur-de-Lys in print, in a Scouting connection, was also at the time of the 1907  Brownsea Camp. B-P had at that time contracted with his new publishers Pearsons to publish both Scouting for Boys and The Scout Magazine. B-P was advanced a sum to enable him to promote the new movement in a series of lecture tours throughout the country in 1907/1908. Pearsons were then very interested indeed in the outcome his Experimental Scout Camp and sent along their Literary Editor Percy Everett (later Sir Percy Everett and Deputy Chief Scout) to observe the last day of the camp. Pearsons also provide Baden-Powell with headed note-paper for the camp which included the term Scouts Campand the unique Fleur-de-Lys pictured opposite. As far as the author is aware the ‘logo’ is unique to the Brownsea camp and whilst a variety of ‘fleurs’ were used in 1909 until the registered design (see below) none of them stood on a central ‘spigot’ rising from a horizontal line below the fleur as illustrated above.

Brownsea Camp. B-P had at that time contracted with his new publishers Pearsons to publish both Scouting for Boys and The Scout Magazine. B-P was advanced a sum to enable him to promote the new movement in a series of lecture tours throughout the country in 1907/1908. Pearsons were then very interested indeed in the outcome his Experimental Scout Camp and sent along their Literary Editor Percy Everett (later Sir Percy Everett and Deputy Chief Scout) to observe the last day of the camp. Pearsons also provide Baden-Powell with headed note-paper for the camp which included the term Scouts Campand the unique Fleur-de-Lys pictured opposite. As far as the author is aware the ‘logo’ is unique to the Brownsea camp and whilst a variety of ‘fleurs’ were used in 1909 until the registered design (see below) none of them stood on a central ‘spigot’ rising from a horizontal line below the fleur as illustrated above.

When Part One of Scouting for Boys was published in 1908, the illustration on the cover was not drawn by B-P, but inside there was an illustration taken from The Boys Scouts Scheme that was B-P’s work. The Scheme, which was published in 1907, clearly shows a Boy Scout with wide-awake hat wearing a very similar two-part badge to the Brownsea issue. B-P proposed that Scouting should be taken up by the Boys Brigade, the YMCA, the Church Lads Brigade and the Public School Army Cadet Corps. The first three organisations (see Brother Organisations) all had Scout ‘patrols’ and all adopted the ‘fleur’ in some form or other, despite having their own historic symbolic badges. Perhaps surprisingly these organis

ations continued with their use of the fleur, despite registering their own brand of Scouting as being totally independent of the ‘B-P Scouts’, until quite late into the 1920’s when they discontinued Scouting as a separate activity.

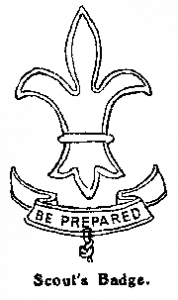

In Part One, the Founder gave an explanation of the badge alongside a crudely-drawn line illustration. “The Scout Badge is the arrow head, which shows the north on the map or on the compass. It is the badge of the scout in the Army, because he shows the way: so, too, a peace scout(sic) shows the way in hiImage courtesy of the National Maritime Museums doing his duty and helping others.” The reader will have noted that B-P did not use the words ‘lily’ or ‘Fleur-de-Lys’ but referred to the badge as ‘the arrow head’.

Baden-Powell’s original design appeared in print on the first Scout Registration cards, issued in 1908, copies of which are kept in the Archives of the British Scout Association at Gilwell Park.

Why did the badge need to be registered?

B-P was a great leader but no businessman. In choosing the word ‘scout’ he used a word freely available in the English Language, and the badge he chose, whether you call it a ‘fleur’ or ‘arrowhead’, was an ancient symbol, so neither could be copyrighted. It was only the two stars with a total of ten points – one for each of the then Scout Laws that made the design one that could be copyrighted, and that is still the case today. At the time, the chief concern was to distinguish Scouts in B-P’s now rapidly-developing mainstream Scout Movement, from those in Patrols and Groups formed in the Brother Organisations. The same organisations that B-P had looked to in order to promote his original ‘scheme’.

France

The Bourbon Royal Family lost the French throne in 1830, but there were many in that country who hoped for a restitution of the Monarchy. Their supporters had formed a political party to overthrow the Republic and bring ‘The Pretender’ to the throne. The Royal ‘fleur’ became their party-political emblem. During the 19th and the early 20th century the government of the French Republic viewed this political movement as a potential threat. French Scouting always explained, underlined and stressed that Baden-Powell’s ‘arrowhead’, that they accepted, was the emblem of World Scouting and in no way connected to the Bourbon Lily. At the same time it could not introduce the ‘arrowhead’ in France because it did not differ significantly from the ‘fleur’ in anything but name.

As early as the Second International Conference of 1922 in Paris, French Scouting placed their dilemma on the agenda. It explained the difficult situation and, with emphasis, urgently requested the other countries present to refrain from using the words Fleur-de-Lys or Lily. The meeting’s minutes records: “The Conference decided that the universal acceptance of the name Fleur-de-Lys for the Scout Emblem was impracticable as in certain countries (notably France) the Fleur-de-Lys has a political significance.”

The only credible alternative name for the emblem was ‘arrowhead’. Every national contingent was requested to use their own translation of the word for their version of the Scout badge. This request, as history shows, was not very well honoured and regretfully the usage of ‘Lily’ and ‘Fleur-de-Lys’ continued until this very day. Baden-Powell, as we have seen, interchanged the two terms freely. Regretfully, as far as many people are concerned, it was his ‘fleur’ derivation that stuck and became part of the Scout vocabulary, for example, throughout the United States. Even Britain, that has had its own new registered design since 1909, continued to use a very French looking ‘fleur’ in connection with our Thanks Badges until 1920 and although we might have then abandoned the use of the lily as an emblem, we have never stopped referring to the Scout badge as the ‘Fleur’. To give a personal example, if at any stage of my Scouting career, I had been asked to define the Scout Badge, I would have said it was based on the Fleur-de-Lys. In Germany the use of the term ‘Lilie’ or ‘Pfadfinderlilie’ is common and the Dutch speaking part of Belgium use ‘Lelie’. They do not really understand why their northern neighbours in the Netherlands, taught their Scouts to use the ‘Pijlkop’ and never, never the ‘Lelie’. In some British territories and Northern Ireland however Scouts stuck to the term ‘arrowhead’, as did the Dutch who used their word ‘Pijlkop’.

In the years between the two world wars the situation became ever more complicated. In Italy, the Fascists began to hold sway and in Germany the National Socialist supporters took control. Fascism had its supporters in most European countries. In France there were several small but fanatic factions, some plotting to bring about a fascist Kingdom similar to that of Italy and, much to the dismay of the Bourbon Family and the Royalist party, they used and besmirched the French Lily as its symbol. In short, from 1910 to well after World War Two (1939-1945) French Scouts could not and would not use a ‘arrowhead’ as their emblem.

Had the French been able to adopt British registered design of 1909, with the two five-pointed stars, it would have provided a Scout badge that was clearly different from the French heraldic device and so overcome the problem. There were several reasons however why this was not practical.

-

- The very act of copyrighting precluded others from using the design.

- Even if exceptions were made, it was not likely that a proud sovereign nation such as France would copy any other nation’s design.

- In any event any one badge, no matter how it was contrived, could not have provided for the various religious denominations that maintained separate but affiliated Scout Organisations in France.

- There are those who believe, even today, that with or without the two five-pointed stars the emblem was a ‘fleur’, and as such repugnant to French Republicans.

It is not to be supposed that opposition to the ‘fleur’ was just confined to the continent. In a letter to Headquarter’s Gazette, July 1927, F W W Griffin, Assistant County Commissioner,London,wrote:

“May I protest gently against the too common custom for describing the Scout’s Badge as a Fleur-de-Lys . . . of French design, without any special significance to Boy Scouts.”

Dr F W W Griffin, who later went on to great things in the Rover Section, preferred the term ‘arrowhead’, claiming this was B-P’s own derivation, which of course it was, but then so was the ‘fleur’.

A book, Les Jeunes Veulent Servir (Youth Willing to Serve) the upper spine of which is shown here, was presented to Baden-Powell at the ‘Coming of Age’ Jamboree at Arrowe Park, Birkenhead, in 1929 by the Eclaireurs Unionistes de France, one of four official affiliated French Religious Scout Organisations, three of which were represented at the Jamboree. Two of the remaining three groupings, Eclaireur de France, whose symbol was a bow and arrow and the Scouts de France, who utilised the Jerusalem Cross, a Christian cross with each ‘leg’ resting on a bar at right angles to the leg, were also present. The book has a personally inscribed message to B-P from the leader of the Eclaireur Unionistes whose name unfortunately I cannot decipher. Clearly the the spine of the book has both the French ‘Coq’, the emblem of the Eclaireur Unionistes – usually to be found in red, and also a very French looking ‘fleur’. The four corners of the front cover also exhibit the same ‘fleur’. This would seem to fly in the face of the arguments presented above, yet there may be a plausible explanation. Though the book, written in French, was published in France, the sp

ecial binding, done especially for B-P, was produced in England. Why this should be is a mystery – France has its share of skilled bookbinders – but the book is clearly stamped Speakman, Binder, Liverpool. Liverpool is very close indeed to Arrowe Park, Birkenhead. It seems to be stretching creditability to think such beautiful workmanship, including the gilding of the page edges, was completed whilst the Jamboree was running, but, I suppose, it is possible. In any event, the gold blocking and motifs were applied in England. It is possible that the cockerel and the French-looking ‘fleur’ were ‘stock’ designs held by the bookbinder, but he may not have had to hand anything looking remotely like a Scout ‘arrowhead’. It is interesting to imagine the thoughts of those who commissioned the binding, on collecting the book, when they found that it was clearly adorned with the image of a French political party which might be taken as an insult to the Republic. Perhaps the proximity to the time when the book was due to have been be presented to B-P cancelled any thought of having it rebound.

The book has the stamp of B-P’s Pax Hill Library, and was at some stage no doubt, given by Lady Olave Baden-Powell to the Guide equivalent of Gilwell Park, Foxlease. How it came from there to be in the lists of a dealer in Scout Ephemera I have, despite enquiries, no idea. The significance of this book to this article is not its interesting life history, but the use of the French-looking ‘fleur’. We would be very interested to learn of any other examples of this ‘fleur’ design by French Scouts that can be definitely attributed to the period ending with the Second World War.

Thankfully the confused and entrenched ideas surrounding the use of the ‘fleur’ did change after 1945. The Fascists and Nazis (it was thought and hoped) now belonged to the past. During the worldwide conflict the Bourbon family had acted as loyal Frenchmen. Some had served in the Free French Army, others in the US Army, and had helped to liberate France. They and their followers understood that the restoration of the French Kingdom had become unrealistic and though the Family never yielded its rights to the Throne, the issue had became an historic political issue, confined to those, perhaps of a nostalgic nature, who liked to maintain the symbolisms of a past age. And so, almost 40 years after its general introduction, French Scouting was able to adopt the ‘arrowhead’ at last.

The Emblem Goes International

Immediately after its official inception in 1908, Scouting could not be restricted to the British Isles and its overseas territories only. Like wildfire it spread all over the world. Other countries simply translated the British rules with some minor adjustments to suit their national circumstances. Their emblems, much to the delight of badge collectors, were often beautiful interpretations of B-P’s basic design, but still instantly recognisable as a Scout badge. In most countries except that is, for France.

Yet, from Scouting’s earliest hour, there had always been those who, in order to underline and emphasize Scouting’s international brotherhood and unity, had propagated the idea of one World Scout Badge to be used by all countries. A good idea no doubt, but for the time was a bit premature as events were to prove. During the Second World War many people had experienced the terrible consequences that rampant nationalism leads to and some distanced themselves from national symbols and promoted international unity at every opportunity: Scouting was one of these.

During the International Committee meeting of September 26th-29th, 1962 the Dutchman Jan Volkmaars, Chief Commissioner and International Commissioner of the NPV (Vereniging de Nederlandse Padvinders) put forward an official proposal to design and introduce one World Scout Badge to be used by all movements. It was a hot item, which was discussed in length by all member countries without resolution until during the 22nd World Scout Conference at Helsinki in 1969, where the following resolution was accepted by all: “05/69. WORLD SCOUT EMBLEM, FLAG AND BADGE”

The World Scout Emblem

In his book Scouting Round The World, John S Wilson, Director of the BSIB 1938-1953, stated, on page 210:

“I did not introduce an International Scout Badge until 1939 – a silver Fleur-de-Lys or arrowhead badge on a purple ground surrounded by the names of the five continents in silver within a circular frame. The wearing of it is not universal, however, but it is confined to past and present members of the International (now World) Committee and the Staff of the Bureau. A flag of similar design naturally followed, the flying of which is restricted.

“The Conference resolves that the World Scout Emblem shall consist of a field of Royal Purple bearing the White International Arrowhead surrounded by a White Rope in a circle and a central reef knot at the bottom, authorizes its use and reproduction by Member Associations and their members in forms not intended for sale, and directs that it be incorporated in the emblem designs of official international events.”

When the new World Badge and Emblem was introduced the old BSIB badge became extinct and is now difficult to obtain.

There were countries who immediately introduced the World Badge as soon as it was available, whilst others were not so keen. They found it difficult to drop their now traditional, sometimes very artistic, membership, tenderfoot or promise badges. Some member nations compromised by wearing both badges. Others were unable to use the new World Badge as they were in a process of going co-educational, in that their National Scout and Guide Movements were merging and consequently a badge had to found that combined the Scout Badge and the Trefoil. One such country – paradoxically – was The Netherlands, the initiator of the single World Badge, but according to the World Scouting Bulletin of December 1973, seventy-five National Scout Movements were using the World Scout Emblem and many others were to follow in the following years.

The World Scout Committee in formulating its Resolution 05/69 sought to end the confusion of the badge’s name. The terms Arrowhead, Fleur-de-Lys or Lily were not used. ‘The World Scout Emblem’ became our new international badge. Its name could easily be translated into any language. There are those who continue use the term ‘arrowhead’, and some countries are still sticking to their ‘Lilies’. It is to be expected that when Scouting is a hundred years old, the situation will still be very much the same! Baden-Powell was very aware that there would be controversy about the origins of his badge in later years, as there had been in his life time. I discovered this note in the UK Scout Archives:

“The badge was that I used for the 5th Dragoon Guards (since adopted throughout the army,) . . . “

From ‘Note for office to be keep in case of revival of arguments later when I am dead’. R B-P 17/12/13

A replica of what is thought to be the original Brownsea Scout Badge. Poole Scout Council, Waterfront Museum Poole

Acknowledgements

- My particular thanks to:

- National Maritime Museum, Greenwich for the use of their copyrighted image of the Adams Compass

- Printed Sources

- Scouting for Boys Lord Baden-Powell of Gilwell. Eighteenth Edition, 1937

- U.K Uniform and other Badges The International Badgers Club

- Internet Sources

- Kroonenburg Piet, From a Toad to a World Emblem